Despite all the joy this sport can bring us, it also brings its share of pain. Whether it’s a recurring stress fracture, a stubborn hamstring, a nutritional Rubix cube at the Ironman distance, or simply the inability to crack a good run off the bike, we’re all broken in some way. Today, in case there’s anyone out there who can benefit from my story, I’m sharing mine. It’s not a cry for pity or advice—I’ve had plenty of both and am grateful. Unless you’re a world-class gastrointestinal motility specialist, of course.

For those of you who know me in real life or as a blogger, you’ve probably heard about the chest monster that attacks every time on the run portion of race. The feeling of trapped air, and suppressed belches, which turn into a tightness and pressure in my upper stomach/sternum area that becomes debilitatingly painful. In short, it makes doing what I love—and is normally fine in training—hurt.

I can’t believe I’m posting this: Not the face of a happy triathlete.

I’ve been told, while lying in the medical tent after the 2011 Big Sur Marathon, that I should get checked out for potential “pre-cancerous esophageal conditions.” I’ve been told it’s GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease) and advised accordingly. I’ve tried Paleo and gluten-free diets, and tested every sports nutrition product on the block. I’ve tried real food, liquids only, and deep breathing. I’ve been told it’s psychological, and that I should try mindfulness based stress reduction (check). I’ve had two sports nutrition consultations. I’ve been instructed to drink aloe vera juice.

For a long time, it was just something I dealt with and tried to troubleshoot in my haphazardly scientific way. I remember lying on the couch after my first 70.3 in 2011 Oceanside, with a good friend who’d never seen me in such a state telling me I sounded like a creaky barn door. After it peaked this year at Ironman South Africa, I knew it was time to deal with the beast head-on. I vowed to do everything I could to figure this thing out, once and for all, even if it meant meeting my deductible. (Done and done.)

Step 1: Esophageal manometry with this baby down my throat for 20 minutes, and me fully awake.

The war story actually started to take shape back in 2012, after I raced Ironman 70.3 Hawaii. I was sitting at the outdoor bar post-race, sipping a virgin pina colada to soothe my chest, and met a friend of a friend who also happened to be Canadian. Our conversation took an interesting turn: When I asked her what she did for work/her visa status (every transplanted foreigner’s favorite topic), she told me she worked at the UCSD department of gastroenterology. I almost fell off the barstool. As we chatted further, she convinced me to make an appointment with the doctor she worked for there, Dr. Mittal.

After waiting a few months (standard), I finally got in that following November. I told Dr. Mittal about my woes, and he suggested that I first try the proton pump inhibitor Prilosec. (Much to my more-hippie-than-I-friends’ dismay, who’ve been suggesting everything from oil of oregano to magnesium to hydrochloric acid supplementation.) I did that, as well as following his suggestion to track of any food triggers, and went on my merry way. He also ordered an esophageal manometry, which I put on hold while I tried some of his suggestions.

Step 2: A panorama of me as a lab rat. (Aka, house of pain.)

After that, I fell back into the same pattern: try remedy X, notice only random, unconnected effects, and formulating more vague hypothesis. I’d notice improvements in training, and then voila! I’d fall apart at a race, vowing I’m going to figure this thing out once and for all. I was buried in that cycle for over two years after that initial November visit, broken up by the glimmers of hope of a handful of “successful” races (like my first Ironman, where I managed to keep the beast at bay with Ensure, of all things).

My second Ironman was worse, but nothing compared to this past April’s race, which I only finished because I’d traveled across eight time zones to get to. I began to wonder, if this was my Ironman cross to bear, did I even want to do it anymore? It was creeping from my chest to my head, destroying my love for racing, and by extension, training. Did I still want to chop wood if I’d never be able to build a house or a bonfire?

Jen as lab rat, part 2 (making a face at Mark).

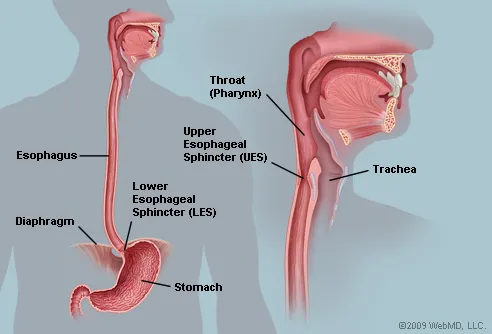

After South Africa, I called Dr. Mittal’s office to schedule the esophageal test he’d ordered two years prior. Though I couldn’t get in to see him until August, I could go for the test in June, the week before racing a half in Syracuse. I had a long tube made up of strain gauges inserted up my nose, past my gag reflex (how fun!), and down my throat. It stayed there for 20 minutes as the nurse instructed me to swallow water, and eventually applesauce, to measure the “motility” or movement and coordination of my esophageal muscles. The procedure (see Step 1 photo) was uncomfortable, but nothing compared to what came next.

In August, I finally had my appointment with Dr. Mittal. He’s a gentle doctor and a good listener, and spent close to 45 minutes with me as I explained the ins and outs of my trial and error. At one point he said, in his lilting Indian accent, “What are you hoping to do with this, do you want to go to the Olympics?” I felt a little sheepish, and expected the classic doctor response, “well, stop doing X.” But he surprised me. My response—that I loved it and wanted to improve—seemed good enough for him.

Step 3: Endoscopy and injection time.

Then, we talked about my manometry test, and I heard him utter the words that anyone struggling with a mysterious medical condition will find oddly soothing: “Actually, you’re not normal.” I knew it! It turns out I have a “nonspecific esophageal motility disorder,” meaning it doesn’t fall into any of the known, named disorders. For unknown reasons, my swallowing muscles don’t move food and liquids through my body properly, which may be causing the tightening or cramping. After that came the comforting words, “we can fix this.”

As if to further cement my abnormality, Dr. Mittal asked if he could study me before treating me. I said yes (perhaps foolishly). If I thought a 20-minute test with a single catheter was bad, this took things to a new level. As you can see in the above photo (Jen as lab rat, part 2) I had not one, but five wires and catheters inserted up my nose and down my throat. One was taking an ultrasound, and to be honest, at this point I don’t even remember what they were all in there for!

I pretended it was an Ironman morning clothes bag.

The irritation of the tubes in my throat became almost unbearable by the end of the five hour study, and my eyes had begun to water uncontrollably. I was so glad Mark stayed in the room with me the whole time, because my vocal chords were so irritated that talking hurt, and I had to speak through texting with Mark. The only redeemable part of the experience was drinking a cold, icy milkshake they used to measure the movement of food through my system. (The worst was blacking out after they administered a small amount of the drug Tensilon into my vein—an experience that I can only imagine came close to what doing heroin or LSD would be like. I saw and heard some weird stuff!)

And then, about a week later, I returned for my upper endoscopy and Botox injection in my Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES). The endoscopy was so Dr. Mittal could make sure everything inside looked normal (the esophageal wall, tissues, etc.) He wanted to rule out things like ulcers and hernias, and happily, he found everything to be 100% normal.)

The Botox injection was his short-term fix/experiment intended to relax the digestive muscles to keep them from cramping. It’s a fairly common procedure, and compared to the initial manometry and research study-turned-acid trip, it was a piece of cake. I was admitted, braceleted, IV’d and wheeled into a room where I was put into a dreamy sleep with no strange noises or colors. It took me a few hours to get back to normal, a process which included dropping (and cracking) my two-day old iPhone 6 while out for fro-yo. Do not leave a new toy in the possession of a post-surgery drunk!

The procedure was on Thursday. Friday I swam 4000 yards in the pool with no issues, and ran 7 miles in the evening. Saturday I rode the Lake Henshaw loop and ran 4 miles off the bike at Kit Carson Park, enjoying the cool change in the air—ahhh, So Cal “fall.”

Riding out East. (Photo by Courtney Clifford Hall)

On Sunday, things took a nasty turn. I couldn’t even make it through 1500 yards in the pool at Masters, and had to get out and move into my own lane. Every time I breathed, my throat and chest tensed up and a belch bubbled up. I’ve also completely lost my appetite in the past few days: imagine feeling that uncomfortable, post-Thanksgiving dinner fullness all the time. Monday, more of the same: an afternoon solo swim that I suffered through, and a nice evening ride with Mark (thank goodness I’m OK on the bike!) Running is basically a suffer-fest of acid, cramps, difficulty breathing, and belching that starts out annoying and becomes painful. (I called my doctor’s office to talk to a nurse. Apparently these side effects aren’t normal, but I read elsewhere that symptoms of reflux occur in about 5% of patients. The fix? Acid suppression. Read: more Priolosec. My poor stomach isn’t going to know what hit it.)

With the Silverman Extravaganza on this weekend (we’re taking a van and sharing a house with a small circus), I’m glad I don’t need to go hard this week. But the idea of not being able to do what I love day in and day out without pain is scary. And as for racing on Sunday, I’m not feeling optimistic. I know, it’s not as if I’ve broken my leg or anything, and I’m trying to be patient and wait it out. I’m trying to suppress the frustration and disappointment and focus on other things going on in my life, like the busiest season ever with work (I fly straight from Vegas to Kona for the Ironman World Championship), and other things that need my care and attention.

So for those of you who’ve been asking and emailing, that’s my story. It’s the monster at the end of my triathlon book (remember that book?) I know, I probably haven’t tried everything, like a naturopath or hypnosis. But first, I’m going with the experts. If they can’t help, well, I don’t know to what extent I’ll go! Things like this definitely test your love for your hobby, and I guess I’m all in. And … at least I’m getting somewhere, even if we haven’t figured it out yet. Movement is always better than stagnation.

Resources:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3623025

http://www.memorialhermann.org/digestive/esophagus

http://www.aboutgimotility.org/site/about-gi-motility/disorders-of-the-esophagus

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffuse_esophageal_spasm

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK54282

http://www.besthealthblogs.us/Inability-To-Burp.html

http://www.medhelp.org/posts/Gastroenterology/i-am-physically-unable-to-burp/show/729008

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Dysfunction-Of-The-Belch-Reflex-We-Cant-Burp/137569112977659

6 thoughts on “we are all broken”